CROSSING BASS STRAIT - BOTHWAYS. FEB ‘82.

Scribe: Laurie Ford

WHY BASS STRAIT?

Bass Strait has a fearsome reputation amongst sailors the world over,

and is littered with wrecks - and still takes a regular toll of modern

day yachts. But a Sea Kayak is not a yacht or a fishing boat, and properly

designed should be able to survive conditions that send larger vessels

seeking shelter. Larger vessels, because of their sheer weight, cannot

rise to breaking seas - but plunge through them, doing major damage to

wheelhouses, rails, and rigging. A lightweight sea kayak will lift to every

wave, and can sit side on to breaking seas with relative ease and safety.

What better place to prove it than Bass Strait.

WHY SOLO?

When conditions at sea become extreme a partner or partners can be

of little assistance as they fight their own battles to stay on course.

In any case many people prefer to do their adventuring solo - Olegas himself

being a prime example. With proper training and experience over a long

period there is little danger in soloing, and there is probably more care

taken than when in a group.

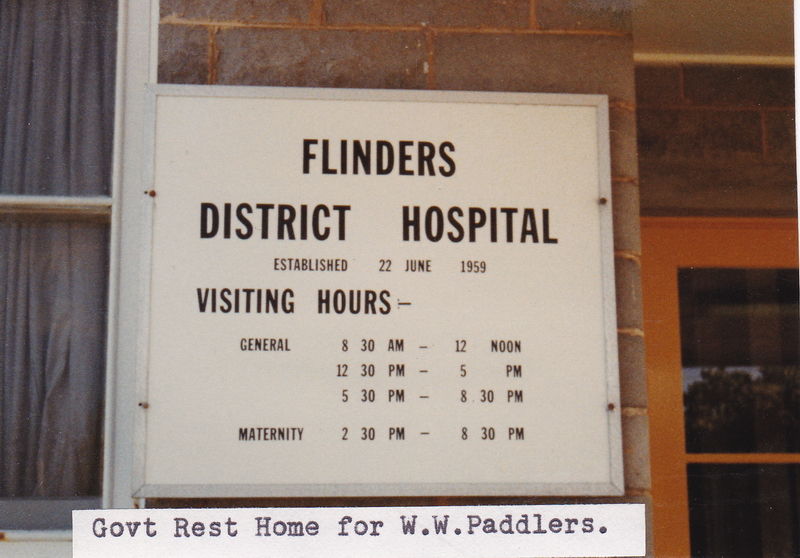

However, this doesn’t mean that any canoeist can jump in a sea kayak - two extremely competent White Water paddlers (Flanagan and Bucirde) failed to go 8 miles to Clarke Island.!

My own experience includes solo trips round S.W. Cape in southern Tasmania; out to Hunter Island in western Bass Strait; and an 18 hour overnight paddle in Storm Bay. All this in addition to regular club trips throughout the past few years. Nevertheless this trip called for special preparation. How much water will the hatches take in over a 24 hour period? How to get the inevitable water out of the cockpit while both hands are firmly gripping the paddle? Tasmanian Sea Canoeists have been making improvements to gear each year and we now feel we have the complete answers to these and many other problems.

D.B. Hatches consist of a vinyl cover over a cockpit type rim, using a double shockcord arrangement to seal them. These have proved their worth on previous trips to Maatsuyker Island and Flinders Island. Recent developments in the electrical field have led to very suitable electric pumps and lighting - an electric pump will empty a full cockpit full of water in under three minutes. The batteries we use will go for six months of normal usage between charges. Combine all this with a proven design of kayak fitted with a rudder and sail and you can go practically anywhere.

Special training leading up to this trip consisted of practising getting back into a capsized kayak. A solo paddler in bad conditions can only do this by getting back in the upturned kayak and Eskimo rolling. My kayak can easily be paddled with a cockpit full of water, and on many normal day trips I don’t bother to wear a spraydeck. Other training was a few gentle night paddles on the Derwent Estuary with some friends. We would regularly set off at 10.00pm to paddle down round the John Garrow Light and back. These excursions were just to harden up the hands a bit and get the shoulder muscles in shape.

The actual crossing of Bass Strait can be done from island to island, with maximum 30 mile hops; and I drove to the north-east corner of Tasmania late one evening. Ready for an early start next morning, the weather forecast was totally wrong - the light south-east actually being a strong westerly, increasing to over 30 knots by midday. With the sail up I reached away across Banks Strait and two and a half hours later tucked in behind Preservation Island, where I landed for lunch. Preservation Island is the site of the first settlement in Australia outside of Botany Bay, and was established when the Sydney Cove ran aground. The island is currently used for grazing cattle, and boasts a neat little shack and a trolley bus. From here I battled on another three mile westward till I called it a day and camped on Cape Barren Island.

The gale continued the next day and I spent the morning walking across to the ‘Corner’. This is the only settlement on Cape Barren Island - consisting of a handful of houses in the north-west corner of the island. Just after midday I poked out into Banks Strait again and made heavy weather of it rounding the western end of Cape Barren Island, with huge areas of breaking water over the numerous shallow reefs. It was a little like a slalom course threading my way past the white water, but preferable to going much further out to clear the area completely. Once away from this hazard I slipped through the channel between Long Island and Cape Barren Island before reaching across Franklin Sound towards Flinders Island. Approaching the island the wind was deflected by Strzelecki Peaks, and with the strong rip in the sound I was swept rapidly sideways. I finally made a landfall on a beach on the southern end of Flinders. As groups of canoeists before me have found, these Bass Strait Islands abound with pleasant little isolated sandy beaches where camping is ideal, and this was one of them.

The third day dawned sunny and windless, and a short easy paddle saw me in Whitemark, the major town on Flinders. Here I reported in to the lads in blue, before being set upon by some friends from Hobart who whisked me away by car to Killiecrankie. This is a beautiful bay in the north of the island - the spiritual home of the club’s commodore. The day remained fine and after being deposited back in Whitemark late in the afternoon I left straight away, and camped at Settlement Point just before dark. Lying in my sleeping bag listening to the transistor radio I was thinking “tomorrow is going to be a great day”, when I sat up with a start. What was I doing - ”today is still a good day”. These days are the exception rather than the rule and sea canoeists must take advantage of good conditions whenever they present themselves. I packed in the dark and headed northwards again, feeling my way past the many islands and rocks that loomed up in the dark. Sometime after midnight I was able to bear away to the east, heading for Killiecrankie where I arrived about 3.00am, and bivvied on the beach. Alf Stackhouse found me asleep in the morning and offered me a hot shower and the use of a caravan, and I used both with much gratitude. I spent the evening with Alf, and Alan Wheatley (a local fisherman) and both agreed with me that early in the morning was the best time to leave on the first long hop - to Deal Island.

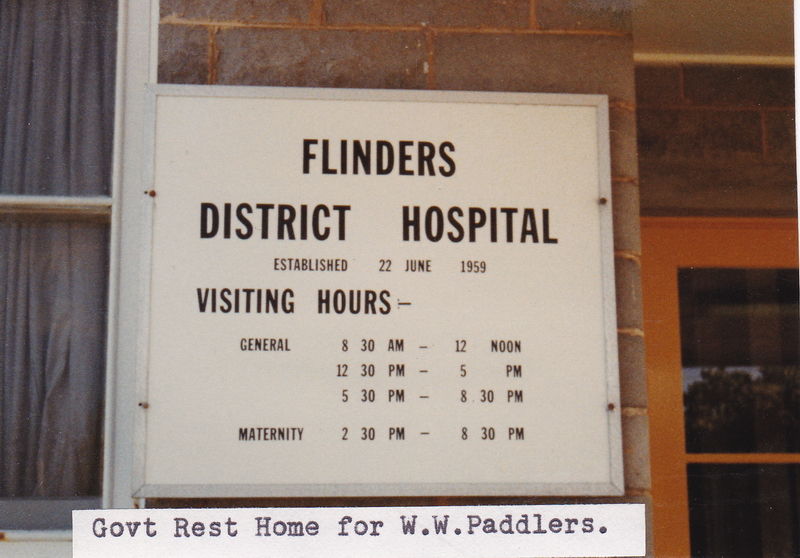

I was up before sunrise and slipped quietly away; out past Craggy Island, Deal Island just a blur in the distance. As the day wore on visibility improved, and Australia’s highest lighthouse was plainly visible, though still far away. Strong tides are a feature of this area and need careful calculation if you are to arrive spot on. My procedure is to estimate the total time for the crossing (based on a paddling speed of 4 knots). I then leave at such a time to allow the tide to take me in one direction for half that period, then bring me back in the other half. During this the time I maintain a strict compass course, and although at times you can appear to be miles off course anyone with a knowledge of maths will realise that this is the quickest way. Attempting to maintain a straight line course is merely time-wasting and energy sapping. The tide swept me close to Wright’s Rock, an extremely turbulent area even in the calm condition, and I was forced to make an effort to clear a particularly nasty looking patch. I was now two thirds of the way across and the weather was holding nicely. Upon arrival off the southern end of Deal Island I decided to keep going up Murray Passage to Erith Island where I had heard some people from Melbourne were holidaying. A light SW breeze wafted in and I used the sail to assist my passage against the strong flood tide. The sail was seen from Erith Island but they could not decide what it was so came out in a dinghy to have a closer inspection. It’s not every day visiting sea canoeists drop in and they were a mite surprised. Immediately upon landing I was treated to afternoon -tea on the beach, the girls bringing it down on trays. They were surprised again when I dragged out my table and stool to sit the trays on, just part of the home comforts that sea canoeists seem to take for granted. The setting was ideal - equal to any tropical paradise.

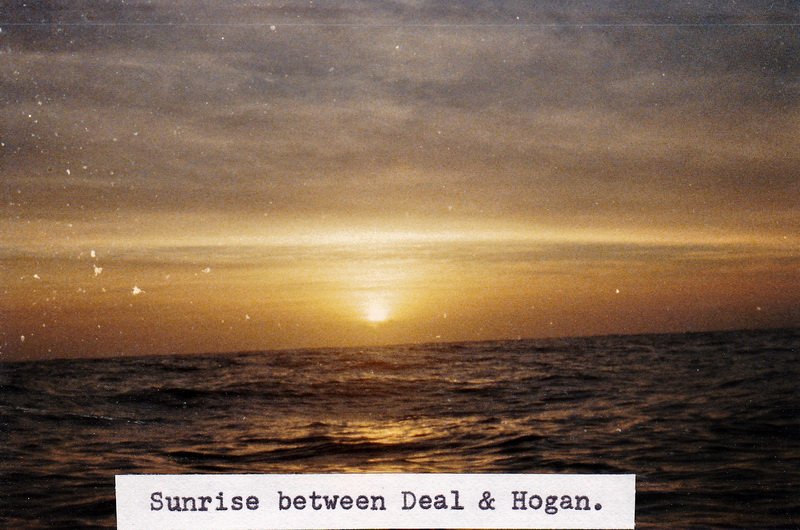

Deal Lighthouse is still manned by two families, some of whom were visiting Erith Island for the afternoon, and I was invited to inspect the museum on Deal if I got across there. Erith Island is used for cattle grazing by Alf & Brian Stackhouse. Just above the beach and they maintain a neat little shack over looking the passage, and let it out to the group from Melbourne every Christmas. I spent a pleasant evening in the shack with the young people. They hire a fishing boat to transport them and a months supplies to the island, and then while away the time fishing, sunbaking, swimming and generally just enjoying life. I bivvied on the beach after promising to call some of them in time to see the sunrise, something they hadn’t quite managed to do yet.

4.30am saw us clambering up the rocky hillside above the shack in the cool pre-dawn chill, which was soon dispersed by the golden rays of the sun as it climbed majestically over Deal Island.

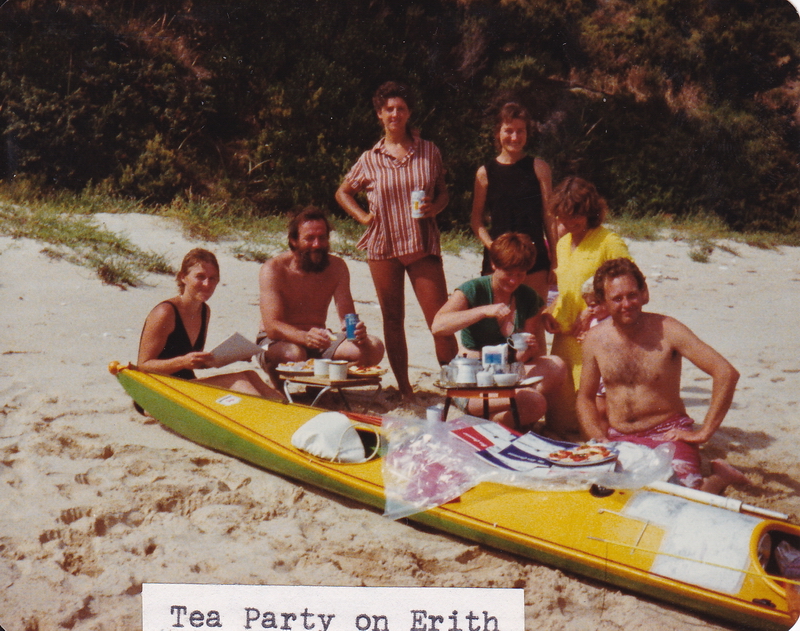

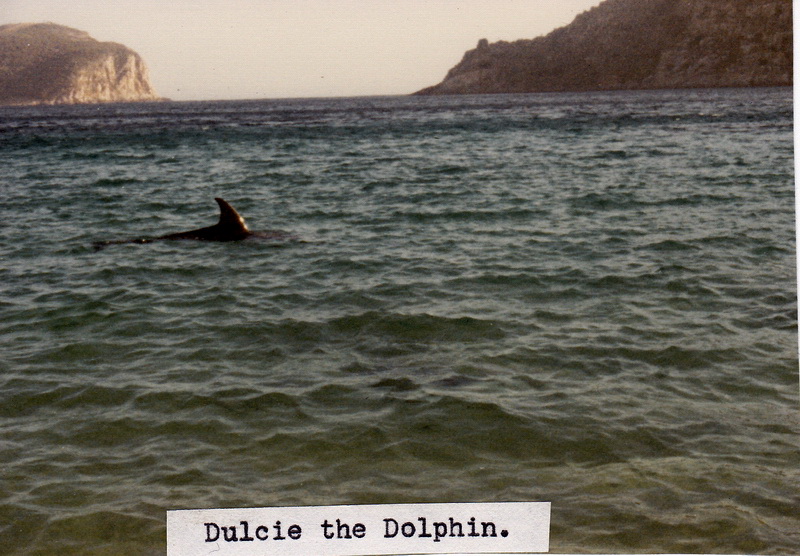

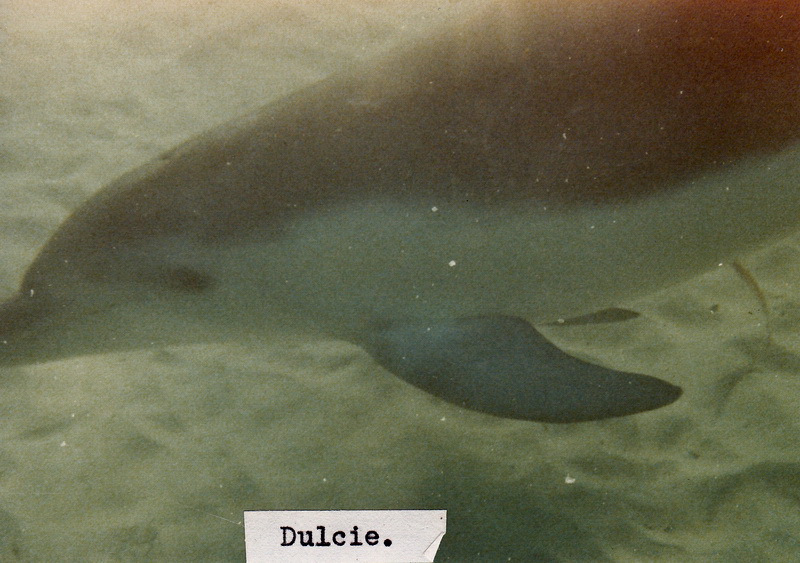

The forecast was for a strong wind, and from the top of Erith looking west the Strait was a carpet of white-horses. I chose to rest on the beach most of the day, recovering from the previous day's excursion. During the day I heard tales of ‘Dulcie’ the dolphin, who had appeared some days ago off the beach and entertained the troops by swimming around in close proximity to them. I took this with a grain of salt, till late in the afternoon I saw a lone dolphin patrolling back and forth 15 metres off the beach. I quickly changed into bathers and plunged into the water with my Minolta in one hand. Dulcie immediately headed in my direction and circled a few feet away. Many’s the time we have encountered schools of dolphins while sea canoeing, but they have usually been going somewhere in a hurry and showed little inclination to show their affinity for mans company as one so often reads about. This time however made it worth waiting for - Dulcie was poetry in motion, one of the most graceful things I have ever been fortunate to see. She adjusted her speed to mine as I followed along behind her, casually coming within touching distance - then a flip of the tail put her just out of reach as I stretched a hand in her direction. We were in about two to three metres of water and at times she would gracefully roll on her back underneath me looking up, her white belly showing as she cruised along. If I turned to swim in the opposite direction she was there in front of me again - one could almost imagine her smiling as she played with this land creature out of his element. Unfortunately it was almost too dark to get any decent underwater photos, and eventually the coldness forced me ashore, leaving me with half an hour of memories never to be forgotten. What beautiful friendly intelligent creatures they are.

A fishing boat anchored just on nightfall, and the crew and I spent the evening in the shack again, before I retired early in readiness for my 2.00am start across to Hogan Island.

My internal clock had me awake in plenty of time to pack in the dark and leave right on schedule. The forecast was for moderating conditions, and once outside Murray Pass I encountered the last of yesterdays chop but it was not unpleasant. Hogan Island is quite low and its light only has a nine mile range and would not be visible for some hours yet. I plugged away on a compass course, now and then passing close to a white blur on the surface. If I came too close to these they would come to life with a start and take to the air. These albatrosses are beautiful to watch in the day-time, never flapping a wing, just riding the air currents a few feet off the water, and one appreciates their enormous wing span as they wheel over head for one look before continuing on their way. Eventually the distant flash of Hogan could be seen now and then when my upward rise on a swell coincided with a flash - then it became more regular. As I drew nearer Hogan Island was plainly visible when the light switched off at sunrise.

I was ashore by 7.30am and felt quite elated - the trip was all but over. It was now only about 20 miles to Seal Island to camp for the night, and then another 8 to the Promontory tomorrow. I changed into dry clothes and walked over part of the island, which is used for cattle grazing. Even in this modern day, life in the islands still follows the old ways - to get cattle off the islands entails towing the beasts into the water with a dinghy and swimming them out to an anchored vessel. Here a sling is put underneath them and winched one at a time onboard - a time consuming process. Hogan is uninhabited and I sat in solitude at its peak next to the lighthouse, waiting for the day to warm up, and report my position, as I had every day - either by phone or by radio. The Sea Canoeing Club has established a good understanding with the Tasmanian Police over the past years. We keep them informed of our activities and trip reports by hand delivering ‘The Sea Canoeist’ to the Search & Rescue Department, and they know they only have to phone Hobart Radio if they wish to establish our position during a trip in a remote area. Although the initial cost was high, the lessening of concern by families at home by regular reports is vital. Two weeks would be a long time for loved ones at home to imagine every possible disaster during a trip along the rugged West Coast. If disaster did strike in the first few days, a search instigated weeks later if or when someone finally decided we were overdue would be of little use. We usually manage a position report every 48 hours, and this arrangement keeps everybody happy.

About 10.30am I set off in the direction of Seal Island, but after half an hour I thought “why not go for the Promontory direct, it’s only about 40 miles?” A quick check of the tides and a rethink on the weather - sure, why not? A slight haze prevented me from seeing the Prom so I just paddled west hour after hour. Several hours later I was still going, but feeling very low. The tops of the mountains had just been visible through the haze for some time, but didn’t seem to be getting any closer. I had been paddling for an hour at a time, with a two minute rest every hour, but suddenly found I just couldn’t paddle for more than a couple of minutes at a time. I persevered for about half an hour but eventually gave up and just sat there. A very light easterly had just started and the tide was about to change in my direction so I decided to just sit there for an hour or so with the sail up and have a good long rest. I got stuck into what food and drink I had handy. This was a really low part of the trip, but seemed more mental than physical.

Half an hour later I started off again, but took another hour to get back into full swing. A few ships passed miles away, but even in the calm conditions I doubt if I was seen. The wind gradually increased and by 6.30pm I flew past the Promontory Lighthouse, having decided to go all out for Tidal River rather than the much closer Waterloo Bay. Up the western side of the Prom the wind became my enemy, gusting down out of the gullies, threatening to whip the paddle out of my hands. Although still paddling strongly I was feeling thoroughly exhausted, and was still short of Oberon Bay when the sun went down. By the time I reached Oberon Bay it was quite dark and the surf on the beach sounded enormous. However it was quite small and minutes later I was safely ashore and warming up in my sleeping bag alongside the Longboat, munching some chocolate.

On the water at 8.30am for the last two miles to Tidal River, and staggered up to the Park Office to book in, ring home, and have a milkshake. Back on the beach I made two or three trips with gear from the water's edge before a holiday maker took pity on me and offered to help carry the Longboat up. He was a bit surprised to hear I’d just crossed from Tassie, and I was invited up for a late breakfast with his family. I don’t normally drink beer with breakfast but the day was already a scorcher and two or three went down very well with the sausages, eggs and bacon. I didn’t really feel like moving out of the armchair, but dragged myself off to the shower before lying down for the rest of the day - smiling now and then at the reaction of the staff when I’d booked in.

When I was proffering money to pay for the campsite this dear lady asked if I’d paid anything when I came through the Yanakie entrance, so I just replied I hadn’t come through the entrance. She then got this exasperated look as if to say “listen you Charlie, if you didn’t come through the entrance how else could you be here?” but actually put it much more politely than that. I then said “I came by canoe - from Tasmania”. I could see her starting to get this look again, as if she thought I was pulling her leg, but then she took in my wet shorts and jumper and finally decided I wasn’t kidding.

As I dropped off to sleep I realised that the worst part of the trip was over - it would be much easier going back. Because the Promontory is 60 miles to the west of Flinders Island, and the prevailing wind is westerly (and strong) you can’t afford to get caught out with the weather as you travel north as there is no shelter to leeward to run for. Going back the other way you can head off in almost any weather and let it take you down towards the islands.

Steve Jacobs and Ray Abrahall arrived later in the afternoon, having left Sydney by car the night before. The next few days were idyllic as we pottered about on land and sea, enjoying all the area has to offer. The following weekend saw a gathering of 15 sea canoeists from four different states, together for two days for a bit of proficiency testing. I was a little disappointed with the standard; there was obviously little thought given to fitting out sea kayaks, or to gear in general.

However sea canoeing is relatively new in Australia, and Tasmania enjoys a coastline second to none that has encouraged sea canoeists for many years. But some of the participants were very keen and we planned further regular trips - the next one from Tasmania to the Hunter Island group in Western Bass Strait, in 12 months time. (This duly came off and 14 paddlers representing 4 states took part in a 10 day trip - it proved a very valuable interchange of ideas.)

Monday morning and it was time to go again, a forecast strong north wind followed by a SW change - what could be more ideal? If the northerly holds out for most of the day I could get out to the vicinity of Curtis Island and then let the change take me across to Deal Island. Steve and Harry accompanied me to the southern side of Oberon Bay but I had to leave the sail down so they could keep up. After they turned back I romped down the Prom under sail, being photographed by a couple of blokes in a big aluminium dinghy - who must have thought I was completely insane. Made Moncoeur Island by 11.00am (18 miles in 2 3/4 hours) but then was absolutely disgusted to see the wind die right away to a flat calm. Only an hour before I’d been surfing down huge waves close to the stern of a container ship. Now I was faced with a 40 mile paddle in a dead calm - no joy at all.

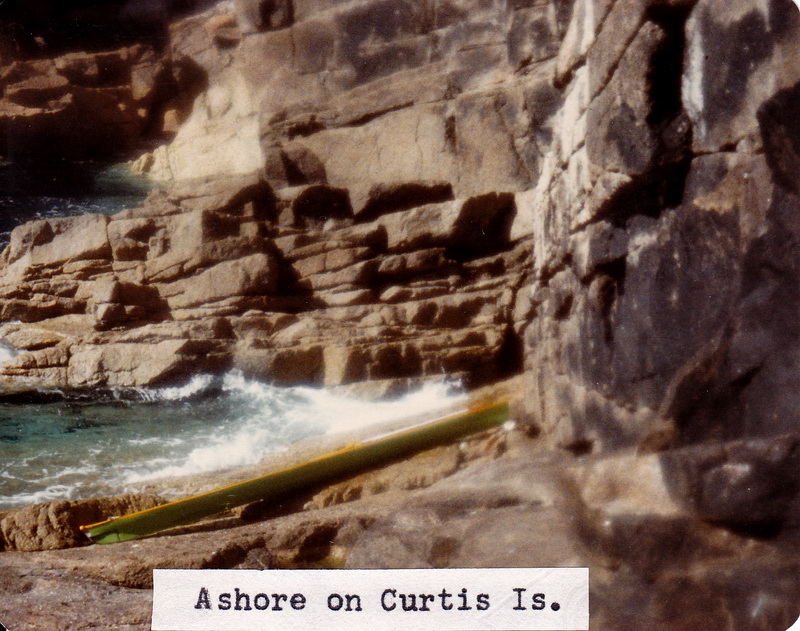

Plugged onwards towards Devils Tower (Deal Is still invisible over the horizon) until mid afternoon when I decided to check out Curtis Island. Fishermen had told me that you couldn’t land on it, but they don’t always realise a sea kayaks capabilities. They were wrong - but only just. With the low north east swell I found one possibility - a small indent half way down the northern side, with a steeply shelving rock I thought I could scramble up it if I could get a foothold. Just under the water was a flattish looking rock, so after watching the swells for a while I rode one in and leapt over the side, only to loose my footing and flounder in the water - then found myself and the Longboat back out in deep water as the swell receded. The next one brought me back in again and I scrambled up the steep slope hanging on to the bow of the kayak, then dropped the paddle and carried the Longboat bodily up the rock out of the waters reach. The only damage done was a bit of skin off two knuckles, and my pride.

It would have been easy to camp, but a slight change in swell direction and I may never leave the island - for all I knew this might be the only day in the year that it is possible to land at all. What were the alternatives? Paddle on to Deal Island (33 miles away) and probably arrive at 3.00am - or go straight out for Flinders Island? I decided that if I was going to have to paddle till 3.00am then I may as well paddle all the way to Flinders and get it over and done with - and got a lot more food and drink out of the front hatch and stored them in the cockpit. I was on Curtis Island less than ten minutes, not wishing to be trapped there. Getting off was a matter of carrying the Longboat back down to the water, waiting for a swell, dropping it into the water and quickly sitting on the back deck as the swell swept out to sea again. A couple of paddle strokes to clear the incoming swell then slip back into the cockpit and put the spraydecks on.

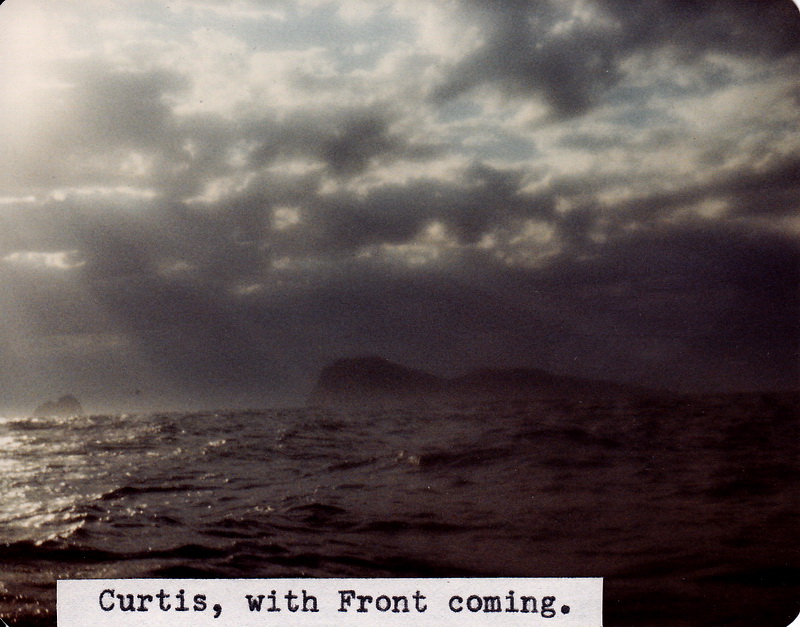

I paddled down to the southern end of the island and most of the way up the other side, but definitely no landing spots. At the southern end the cliffs appear to rise the full 1,100 ft sheer out of the water, a formidable sight indeed. It was 5.30pm when I left Curtis, with the predicted cold front extremely visible away to the south west. I laid a course for a few miles south of South West Island - thinking to keep within striking distance of Deal Island just in case, but a fresh north easter blew up at nightfall. Rather than fight it I eased away to the south east to be in a good position for the change, which was slowly invading the sky.

It’s a very lonely feeling out in the middle of nowhere as it gets dark, knowing you are in for an all night paddle with a fresh change on the way; one keeps wondering whether one’s judgment was correct, or whether one was about to add to the unsolved list of those missing at sea.

The change had two or three attempts over a few hours to blow in, but kept dying away to be replaced by the light north easterly. Eventually about 2.00am it came in hard and steady, starting off southerly, gradually going round to the west during the early hours of the morning. I had the sail up the minute the southerly came in and reached away to the east, trying to make as much southing as possible. Later on it swung around and I found I could lay south quite comfortably, and eased off to about 120 degrees, hoping to be well west of Flinders Island by daylight. The seas built up rapidly before the 25 - 30 knot wind, and the Longboat revelled in the conditions, running diagonally down wave after wave.

Then the impossible happened - I started dozing off. I would have thought that the motion of the boat, plus the spray whipping across the deck would have kept me awake without any trouble, but for the next two hours I battled to stay awake. The compass was just a blur - by peering right forward I could distinguish the E and S, but the three number figures in between were just a blob of white. I have dozed off on a night paddle before, but in fairly calm conditions. At that time I am fairly sure I continued to paddle while asleep, maybe three or four strokes at a time. This time I also survived by instinct. Many times I woke with a start to find the Longboat off balance, only to realise I had already performed a support stroke automatically. The Longboat is a lot more stable than people realise, even with the sail up under these conditions. Taking it down would have reduced the tendency to capsize considerably - but from my experience last time I knew the compulsion to sleep would go. The automatic support strokes slowly boosted my confidence, but it was still a relief two hours later to snap out of the sleepy feeling. A fishing boat that had been off the west of Deal Island all night slipped past me half a mile away just before dawn, heading back to Flinders, and I wondered what my decision would be if it sighted me and offered me a lift. I guess I would have continued to paddle, but was glad I wasn’t actually put to the test.

I’d been expecting to pick up Craggy Light, or maybe even Goose Island Light, but neither appeared, and Deal Island disappeared in the gloom well before daybreak. As the sky lightened I found I was alone in a grey sea, with low cloud all round the horizon, not a thing in sight - so where the hell was I? After a bit of careful guesswork I decided I had to be to the west of Flinders Island and could afford to run off to the east for a while. An hour or two later as the sun rose a bit higher, the cloud started to disperse slightly, and the odd bit of land and islands appeared straight in front of me, about ten to fifteen miles away. I couldn’t make out any landmarks from so far out so held my course till the beaches and headlands were distinguishable as such. Still some cloud about, and nothing looked familiar. I somehow had the idea I was coming in towards Whitemark, but it was only now and then when you were up on a crest in the now large swells that you could take a quick glance. The first couple of beaches looked deserted so while still a fair way out I altered course to the north slightly, to get round the next large point.

This next beach was also deserted so I decided to run in behind the point and take a good look at the chart and compass and try and work out where I was - running along in these big seas it was impossible to study the chart closely. Running in round the point the seas were almost vertical, about 30 feet high, and I was continually holding the paddle above my head to stop it being forced under the water by the breaking seas. It wasn’t actually terrifying, but was getting a bit hairy, and I was glad to get in under the point and lower sail, finally arriving after 26 hours - but arriving where? Now that I could look out to sea I immediately picked up Craggy Island, just visible, and a compass bearing put me in behind She-Oak Point - damn and curses. The first beach I’d run past had been Killiecrankie, but I’d been too far out to see the boats anchored there, and the couple of houses tucked away at one end of the beach. I could now either slip into the beach where I was and camp till the weather moderated, or battle back against the westerly seas to Killiecrankie. I checked the tide tables and found that the ebb tide would also be full against me as well, so the obvious decision would have been to camp. Not being one to always do the obvious, and still feeling 100% fit I decided I wasn’t stopping till Killiecrankie, and headed out around the point. Head down, partly blinded by the spray, I gave it heaps for about 15 minutes, then had a quick glance back over my shoulder, thinking I must be halfway across the bay - HA! I’d gone about 100 yards, and was virtually standing still - the tide must be at least four to five knots. Head down and give it to her a bit harder, continually bracing into the big breaking seas, and painfully edging my way out to sea to keep clear of the reefs. My 100% fitness was now about 10% and rapidly decreasing, but it was impossible to let up for even five seconds - thank goodness I didn’t have to stop paddling to pump out. An hour after leaving She-Oak Point I was still only part way across the bay and began to doubt my ability to reach the next point. But the tide had to be decreasing slightly by now and I began to conjure up visions of a hot shower and a cold beer.

After the most gruelling 2 1/2 hour paddle of my life I crawled ashore on Killiecrankie Beach, a mental and physical wreck, and treated myself to a small nervous reaction as I walked along the beach to get my shore legs back. I’d done it, non-stop, as planned some months ago, travelling through the night in a near gale. I later found out that Alan Wheatley had been putting down crayfish pots off She-Oak Point quarter of an hour before I arrived there, and for the first time in his life he had put his lifejacket on. I can’t ever remember seeing a fisherman in a lifejacket, so it gives you some idea of the atrocious conditions. But I’d done it - not just one way, but both ways - the rest of the journey back to Tasmania should be a piece of cake.

I had trouble talking to Alf a few minutes later as he rowed ashore from his 50 foot yacht, but accepted his offer of a shower. The shower and a bite to eat restored me to normal, so I hired a car for the rest of the day to go off and find the others - they were scheduled to leave Whitemark today on the start of their trip. Alf had a message from Rusty that they were to camp at Big River that night, so I drove off that way. Fortunately I had to go past Whitemark so called into the pub and had a couple, and found out that the others had only left in the last hour or so.

A drive to Big River and an hours wait on the beach still saw me sitting by myself, so I gave it away and started checking out all the beaches on the way back, finally finding them at Trousers Point just after they arrived there.

We had a beer or two, and made arrangements to meet on Clarke Island in 4 or 5 days for the short paddle across Banks Strait. I left them just before dark to drive back to the top end of Flinders. Now the lack of sleep started to take its toll as I felt like dozing again, and kept seeing things on the road that weren’t there. However I made it back safely and retired to the caravan for a well-earned sleep.

I hired the car again and drove around parts of the island, to Patriarchs Inlet, and down to Lady Barron where I had a counter lunch. The wind was still quite hard, but I planned to leave the next day just before daylight, to beat the tide round Cape Frankland.

Slept in and missed the last of the tide, so walked the full length of the beach to Stackies Bight, till 2.00pm when the tide was again in the right direction. Not that the tide would be much help, but at least it wouldn’t be assisting the 25 - 30 knot winds that were still whipping up big seas from the west. Alf was a little doubtful that it was really suitable weather for rounding Cape Frankland, but after two nights in the caravan I felt I would get fat and lazy if I stayed another night. A couple of hours later I was regretting this decision, particularly as the forecast for the next day had been for moderating conditions. The seas off Cape Frankland were huge, there is no other word to describe it. I have been out in big seas off the south-west coast before, and tried out a 50 knot gale in Bass Strait off Low Head - but this was terrifying. The westerly gale was meeting a shallow bottom and a 6 knot tide, and it took all my concentration to hang in there. At the bottom of the swells I was looking up a 60 degree mountain, a good 40 feet high, taking 8 to 10 paddle strokes to reach the top, then having the bow drop about 8 feet down the other side before hitting the water again. Usually about half-way up the slope the top would topple and a wall of white water would come careering down to check your upward rise, often flattening you along the rear deck. Progress was slow, it was imperative to keep at least half a mile off shore - any closer and the Longboat would have been fibreglass splinters amongst the breakers in the shallow water. I was sort of ferry-gliding along the shore, rounding up into the worst breakers, then bearing away again. I would have dearly loved to whip out the camera to photograph the conditions, but for three hours was not game to even take one hand off the paddle for more than a second, and then only to flick the pump switch on or off.

It was a bit of a relief to get around the Cape and start running before the storm, but still needed lots of concentration. I thought I’d run in between Royden Island and Flinders and get some shelter as soon as possible, but the seas got larger and larger, and I was confronted by a wall of green water breaking across a half mile front. This wasn’t visible till fairly close, and I hurriedly searched for a way through, to no avail. There wasn’t even a remote possibility of getting through unscathed, the dumpers looking like the Great Wall of China. I about faced and slowly made my way out to sea again, and tried the next passage between Royden Island and North Pasco Island. Although there were many reefs through here it was a relatively easy paddle into the smoother water of Marshall Bay, and I made my way into shore to camp for the night, feeling a great sense of exhilaration after such a battle.

The next morning the wind and seas had moderated considerably and I ran straight down the coast to Whitemark, arriving a few minutes too late for a counter lunch. Not being deterred so easily I sat around in the pub for most of the afternoon waiting for tea time, sallying forth a couple of times to make phone calls, and to buy a few books to read. I anticipated a few days wait before I met the others on Clarke Island, and was looking forward to setting up a permanent camp for a few days and doing absolutely nothing. Back on the beach just before dark and starting to pull my camping gear out when a couple of cars drove up. Leedham & Judy Walker had come down to watch the sunset, and after an inspection of the Longboat invited me home for the night. This was very welcome, particularly the hot shower, and I enjoyed a comfortable night.

My hosts were up early to prepare breakfast, as I was after an early start to use the predicted following winds. The forecast was correct and Leedham & Judy waved goodbye as I sailed straight for the western end of Cape Barren Island, then down the coast to Preservation Island. The wind freshened during the day and at my lunch stop on Preservation I heard the forecast for a gale in Bass Strait. In view of the shack and Trolley Bus here it seemed the logical place to stay for a day or so, so I hauled the Longboat up alongside the shack and unpacked. The shack was not locked and I felt sure the owner would not object to my using it for a couple of nights in view of the circumstances. The shack was furnished with padded chairs, a kitchen table, cupboards, mattresses etc., and the windows commanded a view across the channel to cape Barren Island.

Just before nightfall a light plane circled the shack - Leedham had said he would fly around and see if he could spot me, and so he had. He didn’t hang around as the wind was still picking up - later on in the evening the sky over Cape Barren was lit by lightning, and I was glad I’d decided to camp here rather than go on to Clarke Island.

Sunday it was still blowing strongly. I didn’t think the others would be any closer to Rebecca Bay than I was and decided to stay another day, reading and generally being lazy. Called Hobart at 0930 on the radio but they couldn’t pick me up at all, even though I was receiving them loud and clear. However Melaleuca Inlet (Port Davey) was receiving me and passed on my position.

Explored part of the eastern end of the island and was returning when a light plane did a quick circuit and then landed near the shack. The occupants unloaded the plane and were at the shack before I was - how embarrassing. I’d left my gear scattered about inside, not really expecting visitors. The plane went off, leaving the owner of the shack, Bruce Benseman, and a gentleman from the Department of Agriculture, Rob Thompson, here for the day. Bruce had come out to spend the day cleaning out the silt from the many water holes around the island, and Rob had come out to have a look at the island. I think Bruce is resigned to the fact that many people use his shack, and took my presence quite well and invited me along with them to tour the island on the tractor. This was one of the most interesting days of the holiday - Bruce had a wealth of information on early history of the area, and pointed out the site of the first settlement in Australia outside Botany Bay. He had also been a professional fisherman for some years and had a wide knowledge of the islands and their currents.

It was amazing to see so much water on an apparently flat dry island - the water just soaks out of the earth in many places around the shoreline. Bruce had built small concrete walls to create ponds of fresh water for the cattle he runs on the island. We spent a pleasant sunny day (but windy) driving right round the island before the plane arrived back about 4.00pm to take them back to Bridport.

Monday turned up fine and sunny with a light northerly wind. After calling Hobart (direct today) and telling them I was leaving I used the tide and wind to breeze down the side of Clarke Island to Rebecca Bay. I still thought I’d be a day or two ahead of the others and was surprised to see two kayaks on the beach as I rounded the point into the bay. Andrew Rust and Peter Newman had arrived a couple of hours earlier, and weren’t sure whether I was still coming or had been and gone. It was a glorious day and we celebrated with a beer while waiting for the afternoon slack water. The best time for the southern crossing of Banks Strait is just before high water but we’d already missed that, so the next best time was just before low water. While sitting around on the beach I learnt that Earle and the rest of the party had hired a truck at Lady Barron to drive their kayaks to Killiecrankie, a couple of them finding the going a bit hard.

Banks Strait was oily smooth and we crossed direct to Swan Island with no trouble although we started to feel the incoming tide during the last twenty minutes. It was easy to see that a couple of hours later it would have been a real battle against the tide race round Swan Island. We landed on the beach next to the lighthouse and changed into dry clothes before walking up to the houses. We were treated to hot drinks and biscuits by Andy Gregory and Beth before going on to make our presence known to Laurie Williams - the head lightkeeper. He had a couple of mechanics staying with him, doing a routine overhaul of all the motors, etc., from the generating plant to the lawnmower. These lads were well supplied with crayfish after some diving off the island and we stayed for supper. Laurie took us down to the lighthouse before we retired to bed on his lounge room floor. Like all keepers - Laurie is well versed in the early history of the island, and other lighthouses, and conjures up visions of incredible hardships in the early days of Australian history.

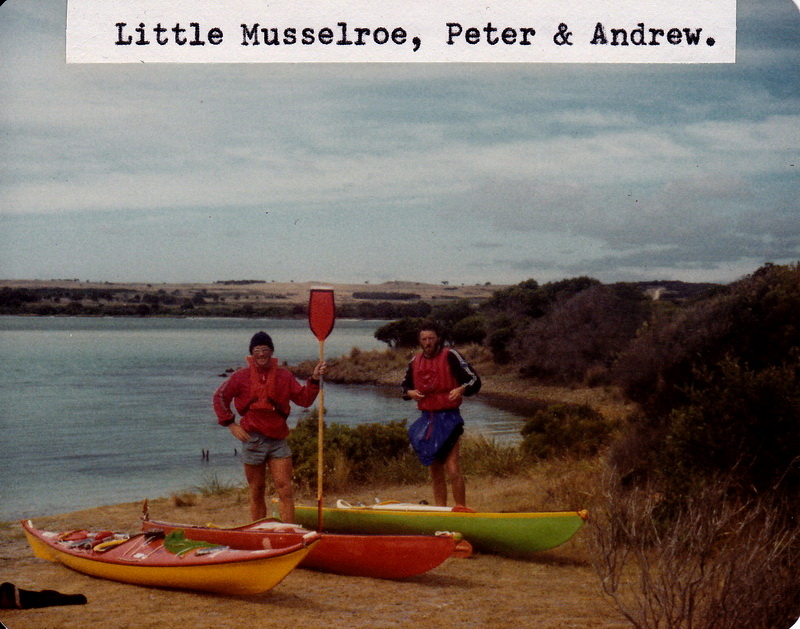

Tuesday 23/2/82 The short paddle across to Little Musselroe Bay the following day was against a fresh westerly, and it was a jubilant threesome that landed about 11.00am. We loaded up the old EH and set off for Launceston via Bridport to look up an unknown sea canoeist who had recently written to the club. Had a shower at the Caravan Park while waiting for Jeff to arrive home, and then continued on to Launceston to spend the night with Jason Dicker, and the evening with John Wilde.

The next morning we got Peter’s Nordkapp off to Melbourne with IPEC, and Peter managed a standby fare on the next plane out of Launceston. So ended a challenge I’d had in mind for some years - careful attention to all details had paid off with a troublefree double crossing of one of the most dangerous stretches of water in the Southern Hemisphere.

FOOD

If you study the Nutrition Chart you will see that nearly all the essential

vitamins are contained in bread, peanut butter, cheese and butter. Over

the past few years I have used these foods almost exclusively on camping

trips. By substituting SAO biscuits for the bread you have a very compact

food supply. As no cooking is required you do not need billies, frypans,

mugs, cutlery etc., and your packing is made much more simple. Tang or

some other form of vitamin C is included to make a fairly balanced diet.

YOUR GUIDE TO GOOD NUTRITION

protein

Every body cell needs an adequate supply of protein for building and

maintaining health. Greater amounts of protein are required during growth

periods - childhood, adolescence, and pregnancy, when new cells must be

formed. Best sources of complete protein are meat, fish, poultry, eggs,

milk, cheese. Vegetable (incomplete) protein is found in soya beans

and other legumes, nuts and cereals. Include some protein at each

meal to maintain good general health.

carbohydrates

Starches and sugars are a main fuel source for most people. Some forms

of carbohydrates, found in plant fibres, help elimination of wastes in

body. “Worthwhile” carbohydrates (which include other nutrients) are found

in fruit, vegetables, cereals and bread - not in syrups, cordial

or sweets.

fats

Fats are the most concentrated supplier of body fuel, add flavour to

food, slow down the rate of stomach emptying, lubricate the digestive track.

Richest source in ‘visible’ form - edible oil, margarine, butter

and fat on meat. Lean meat, egg yolk, nuts, milk and cheese also

contain some fat.

calcium

Calcium is needed by people of all ages for good bones and teeth; clotting

of blood; functioning of muscles, and it also helps nervous system. Milk,

cheese

and fish with edible bones (such as sardines or salmon) are best sources.

Calcium in milk is combined with nutrients which favour absorption.

iodine

Needed for correct functioning of the thyroid gland to prevent goitre

and also regulate energy. Sea foods are richest suppliers of iodine. Content

of iodine present in cereals, vegetables and milk varies in different areas

depending on soil content.

iron

Needed to form haemoglobin in red blood cells, which carry oxygen from

lungs to all body tissues. Found in liver, kidney, hearts, other meat,

poultry and egg yolk. Dried beans, wholemeal bread, green leafy vegetables,

molasses, nuts and dried fruits contain smaller quantities of iron.

sodium

Maintains the correct water balance in the body. Found in poultry,

eggs, olives, salt, fish and meat.

potassium

Helps keep fluid balance, aids muscles and nerves. Fruit, vegetables,

fish, meat, cereals are sources.

phosphorus

Works with calcium to keep bones and teeth strong, and also helps fat

do its work in the body. Obtained in milk, cheese, poultry, wholegrain

cereals: also in fish, nuts, dried beans and peas.

magnesium

Helps transmit nerve impulses, helps muscle contraction, necessary

(as it works with calcium) to promote strong teeth and bones. Cereals,

meats, dried beans, nuts and milk all contain quantities of magnesium.

Vitamin A

Needed for growth and development, healthy skin, vision in poor light,

helps prevent and resist infection in the mucous membranes. Found in liver,

milk, cheese and egg yolks. Carotene, found in yellow fruits and

green and yellow vegetables, converts to vitamin A in the body.

thiamine

Essential for use of carbohydrates in the body, and for the correct

functioning of nervous system Yeast and vegetable extract, pork, nuts,

egg-yolk, wholegrain cereals, wheatgerm, dried beans and peas are all good

sources of thiamine vitamin.

riboflavin

Essential for the metabolism of carbohydrates and protein, also for

growth, vigour, good digestion, healthy skin and for maintaining good vision.

Food rich in this vitamin are milk, cheese, liver, heart, kidney,

eggs, wheatgerm, yeast and vegetable extracts. Sun can destroy riboflavin.

niacin

Required for release of energy in body, for healthy nervous system,

skin, and digestive tract. Found in meat (especially organ meats), fish,

peanuts, yeast and vegetable extract, legumes and wholegrain cereals, also

in peanut butter.

Vitamin C

Needed for the formation of a cement like substance between the cells.

Also needed for healthy blood vessels, teeth, bone, and cartilage. Best

sources are citrus fruits, blackcurrants, pawpaw, rockmelon, tomatoes,

red and green peppers, and fresh broccoli and brussel sprouts.(Tang)

Vitamin D

Helps body make proper use of calcium and phosphorus in the formation

of teeth and bones. Can be made in the body when skin is exposed to sunlight.

Also in sardines, fish liver oils, and in dairy products and eggs

in small amounts.

vitamin B6

Assists body to use protein and maintain the normal haemoglobin level

in the blood. Found in meats, wheatgerm, liver, wholegrain cereals, kidney;

also in soya beans and peanuts.

Vitamin B12

Produces red blood cells and builds new proteins. In fish, cheese,

eggs, meat, milk, liver and kidney.

Vitamin E

Function not fully understood - but is thought to help form red blood

cells, muscles and tissue. Richest sources are wheatgerm oil, cereals,

leafy green vegetables, nuts, eggs, and margarine.

Monotonous? I don’t find it so, and find the simplicity of it all outweighs all else. A meal can be prepared and eaten in under ten minutes, so more paddling time is achieved. I left Tasmania with eight packets of biscuits, peanut butter, four packets of cheese, several chocolate bars, packets of Tang, two dozen cans of beer. In reserve I had a dozen cans of ENSURE PLUS ( a liquid meal used in hospitals), and two packets of Rosella mince (and a billy). Apart from an occasional counter lunch, and doughnuts and milkshakes at Tidal river I lived entirely on biscuits for three and a half weeks, and arrived back in Tassie feeling extremely fit and well - having lost a few pounds weight.

Navigating Equipment

Chart 1695A was used exclusively, and Admiralty Tide Tables. A normal

liquid filled gimballed compass is built into the deck and illuminated

by an electric light operated from one of the waterproof switches on deck.

For navigating at sea I used a Portland Navigational Protractor, a handy device that can be used with one hand, and can be stowed in a pocket sewn on the buoyancy vest.

Other Gear

One change of dry clothes for camping in, tent fly, sleeping bag, sleeping

mat, gortex bivvy bag, table and stool, HF SSB radio, transistor radio,

food, machete, first-aid kit, repair kit, matches, candles, pens, paper

etc..

The Longboat

A sea kayak I designed myself back in 1978 for a trip down the West

Coast of Tasmania. At that time I was not 100% happy with other kayaks

and chose to make major alterations to the one I liked most. It was extended

out to twenty feet, and the underwater shape changed to make it more stable.

Although only twenty-one inches wide it is stable enough to stand up in

in calm water, and I regularly paddle it sitting on the rear deck. Getting

on and off Curtis Island would have been near impossible in any other kayak.

A sail was fitted to assist when the wind is behind, and it can be put up and down with one hand. The sail is permanently fixed to the mast which fits in a socket on the deck. When not being used it slides into a plastic tube along one side of the deck. If you capsize with it up you merely reach forward and pull it out of its socket and then roll up.

The waterproof switches are mounted next to the sail tube for protection during rescues. The sealed battery mounts behind the seat against the rear bulkhead, while the bilge pump is fixed between my legs - the outlet being high on the foredeck. The rudder is built into the skeg and protected by a stainless steel rod. When the boat was layed up extra pieces of wood were glassed in to take the screws for the stainless rod - there is no danger of these coming out and leaving holes in the hull. The rudder wires run through a continuous plastic tube up to the footrest.

Conclusions

It seemed such an easy trip that I would have been worried that others

may have been encouraged to attempt it without previous experience. However

I feel that Flanagan and Bucirde’s near death (another half an hour and

it would have been dark and they would not have been rescued), and Bloomfields

curtailment of his Flinders Island trip has shown that Bass Strait is not

a place for beginners - even if they are experienced white water paddlers.

Sea Canoeing demands a totally different mental attitude, and different

techniques and equipment to other forms of canoeing, and experience takes

years to accumulate. There is no crash weekend course for sea canoeists.

When I do the trip again not one item of equipment will be changed, but I would allow more time ashore. This time I had to be at Wilson’s Promontory by a set date, and had little time to spend on the various islands meeting the inhabitants - and I need to go back again to savour more fully their friendship and hospitality.

The Longboat was superb in the bad conditions, and needs little improvement.

Maybe a more comfortable seat if twenty-eight hour trips are anticipated

again, although it more than adequate for normal day trips.

|

(nautical miles) |

(Hrs) |

(knots) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Paddles

Personally, I prefer a long paddle that gives a long, slow stroke and

have never used a “bought” paddle in my canoeing career. Quite a few of

my colleagues use expensive Lendal paddles, but there seems to be little,

if any, advantage. My one and only “sea paddle” has blades 12cm by 60cm.

I have found that the pointy ends tend not to cavitate as much as a square

end, the whole blade is completely flat, in fact the ‘mould’ was cut out

of a piece of masonite (hardboard) and given a few coats of wax. The dotted

part of the shaft is a piece of 25mm hardwood dowel, planed down slightly

flat on one side to sit on the mould better, leaving about 75mm sticking

out at the end. This will fit very neatly inside a 1 1/8 inch aluminium

shaft and is held in with 24 hour Araldite (don’t use the 5 minute type

- it’s not waterproof). This has a couple of advantages worth considering

if you intend making your own. Firstly, both blades can be layed up at

the same time (if you cut out two moulds) and you are not trying to lay

up at the end of a long, awkward shaft.

When it is glued into the shaft, the shaft is absolutely sealed and

will never leak. My own, now about two years old, has stood many tests

without failing; and also has two hand-grips made of heat-shrink plastic.

Laurie Ford